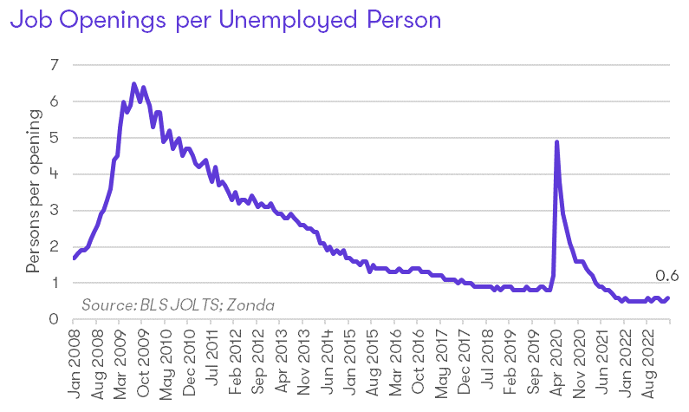

As the pandemic struck the United States, unemployment soared with over 17 million people losing their jobs between February and April 2020. However, as the economy recovered, the U.S. moved from a labor surplus to a fairly significant shortage.

In fact, as we can see from the latest Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Job Openings and Labor Turnover (JOLTS) data, there are 0.6 unemployed people per job opening, meaning there is roughly one person available for every two job postings. Notice, though, that there was a downward trend before the COVID recession, indicating that, even prior to the pandemic, the U.S. was moving from a surplus of labor to a shortage.

The civilian labor force participation rate, the percentage of the non-institutional population 16 years and older that is working or actively looking for work per the BLS, emphasizes this point. Despite recently rising, it remains close to a level last observed in October 1977.

The prime age labor force participation rate, an important cut of the data only looking at those 25 to 54 years old, has returned to its pre-pandemic level at 83.1%. The current rate is down from its peak of 84.6% in January 1999.

The change in the labor force is of particular interest to the construction industry. From the JOLTS data for the whole year of 2022, job openings in construction industries averaged 402,000 per month. This is up about 45% from 2018 when there were 277,000 openings per month on average for the year. There are signs that there’s a better availability of workers since housing starts are down cyclically, but the lack of labor is a longstanding issue.

The obvious next question is “Where have the workers gone?” We attribute the change to four main things: the aging workforce, changes in immigration, drug abuse, and alternative employment opportunities.

1. Aging Workforce. Prior to the pandemic, the 55+ labor force participation rate stood at 40.3%. Three years later, as of March, the participation rate has dropped to 38.6%. As the pandemic unfolded, many baby boomers retired early or took an opportunity to take an extended break. There is conjecture that these workers could “unretire,” but this has not shown up strongly in the data yet.

More systemic, though, is the fact that by 2030, all baby boomers will be of retirement age. This will lead to additional pressure on the labor force as the overall workforce ages and the generation behind them, the Gen Xers, are smaller in terms of sheer size.

The BLS forecasts that the total labor force will still grow through 2031, but with the growth primarily driven by workers aged 55+. This suggests that more people will be working longer and at older ages. Combined with generally falling fertility rates, the U.S. will face demographic pressure on both ends of the spectrum as the workforce ages.

2. Immigration. Immigration has traditionally been a way to help augment the domestic labor force. However, the most recent data from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security indicates the number of people seeking permanent resident status has fallen 37% from its recent peak in 2016. Full year data from 2021 showed a slight increase over the pandemic trough, but immigration is still down substantially compared with pre-pandemic levels.

The shortage in labor is viewed as severe enough that immigration looks like the most prominent short-term solution. Goldman Sachs also argues that immigration is needed to get the labor market back in equilibrium but is pessimistic that the issues in immigration law will be resolved swiftly enough to alleviate the shortage, at least in the near term.

3. Drug Abuse. The opioid epidemic is another contributor to the constrained labor pool. Opioids have been identified as a significant cause of death in the U.S. and, in turn, declines in labor force participation.

The Congressional Budget Office recently published a comprehensive report detailing the crisis as well as the federal government’s response to the situation. The report found that, cumulatively since 2000, 556,000 people have died of opioid overdoses. Not only is this a terrible human tragedy, but this also has adversely affected the number of people available to work.

Additionally, other people that are facing addiction, but have not died, are also unavailable to work. Some studies have put this number as high as nearly 900,000 additional workers unable to work due to various addiction issues.

4. Alternatives to Traditional Work. Lastly, with the rise of TikTok and older platforms such as Instagram and YouTube, there has been a segment of the workforce that is making money online. Based on available data, there appears to be a small portion of the potential workforce that may have dropped out to try to earn income on various social media sites.

According to the Small Business Blog, there are 20,000 to 40,000 influencers on Instagram with more than 1 million followers and 300,000 to 2 million that have more than 100,000 followers. It is unclear how many of these influencers are based in the U.S. and how many of them would solely rely on social media channels for their income. However, the existence of these alternative career paths may be enticing some younger workers to not seek out formal employment.

In addition to the aforementioned reasons, we explored the role of military service and college enrollment in the declining labor force. Right now, the military isn’t a main culprit. The military has recently had a difficult time meeting its recruitment goals, which makes sense as enrollment normally ticks up during slower economic times.

College enrollment isn’t a clear reason either. The Census Bureau’s latest data shows that college enrollment is still below pre-pandemic levels. Notice that undergraduate and two-year college enrollments are down significantly from their respective peaks in the 2010s, although graduate enrollments have been steady and even increased slightly.

Taken all together, many factors are contributing to the problems with the U.S. labor force. A big part of this is the aging of one of the largest segments: the baby boomers. As more boomers retire, further pressure will be put on the younger segments to increase workforce participation and economic output.

Other factors also also putting downward pressure on labor force participation, including slow domestic population growth, lower levels of immigration, drug addiction, and alternative career paths. We also know that those suffering from long COVID symptoms may be contributing as well as those dropping out to take care of family needs.

In addition to the general strain on the workforce and economy, the labor shortage is strongly affecting the construction industry. With an estimated shortage of over 500,000 workers, resolving the U.S. labor supply issue is of utmost importance to help keep home building costs down and to produce homes at a quick enough pace to keep up with demand.

This story originally appeared on Livabl’s sister site BUILDER Online.